Swansea History - An Overview

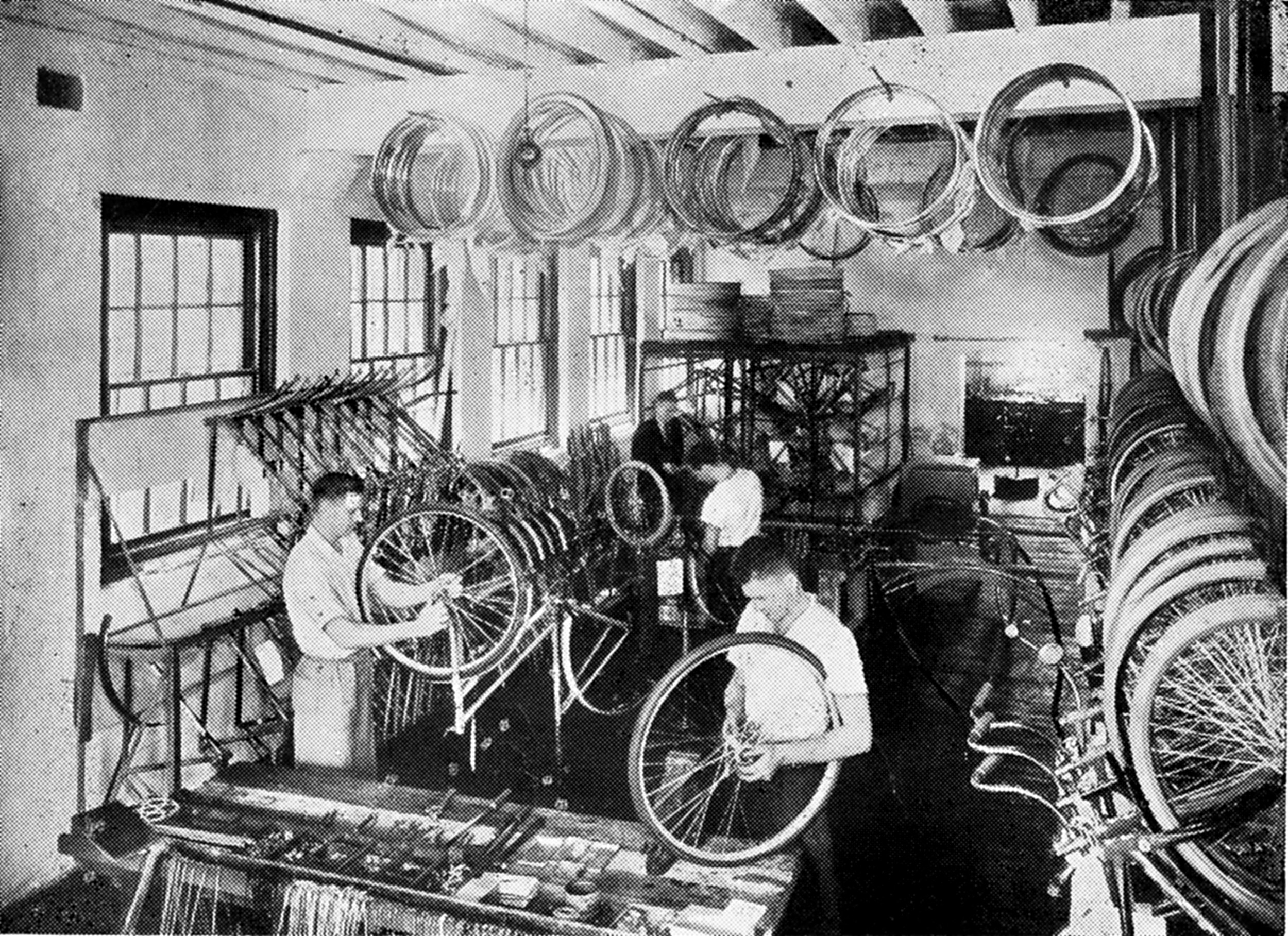

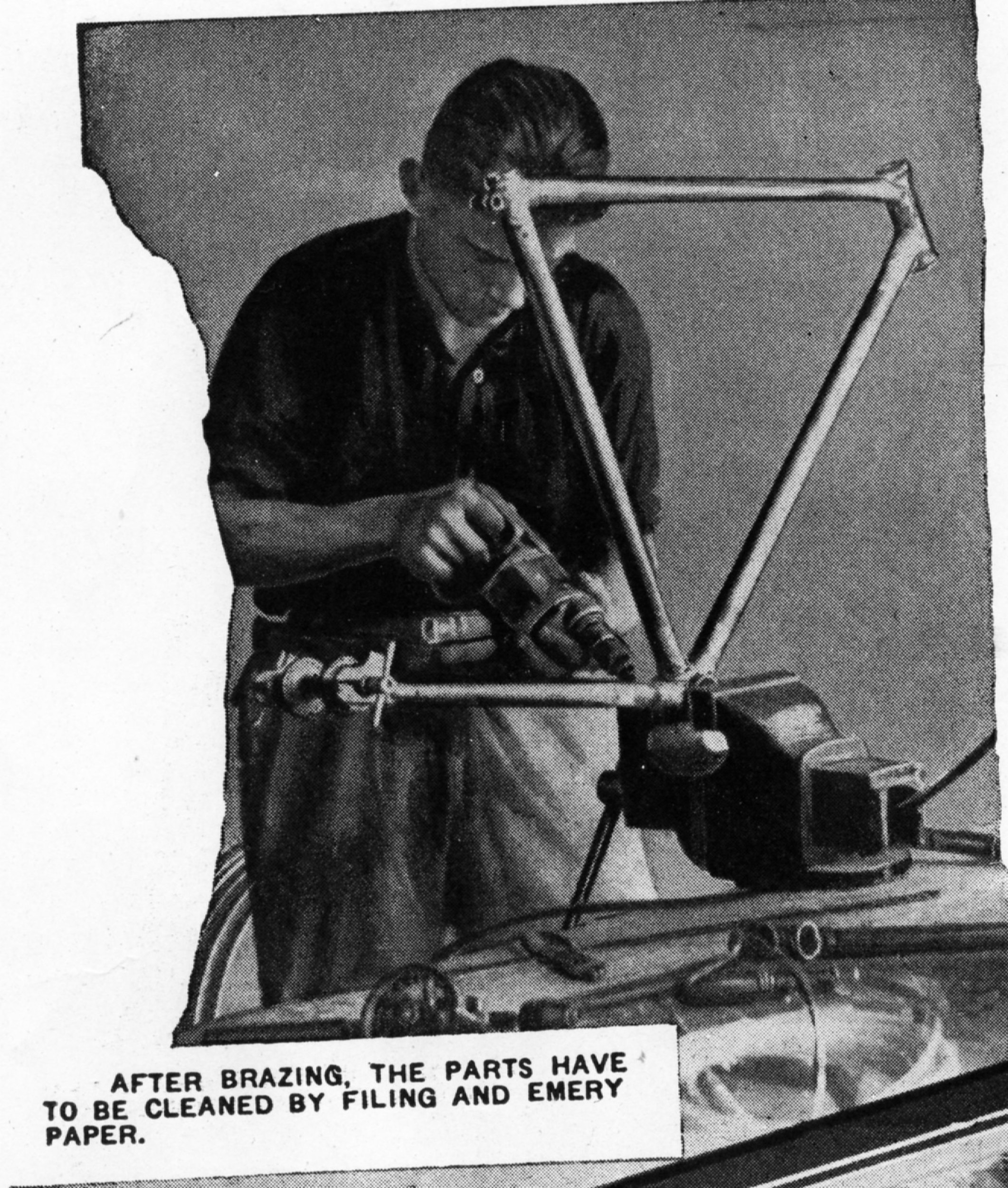

Howard and Les Baldwin were in their early twenties when they set up Swansea Cycles and Motor Co., naming it for their home in Mosman Park, a Perth suburb nestled between the Swan River and the Indian Ocean. They started business at 9 William Street, Fremantle, with a small annex at the rear of the shop where they began making their own bicycles using components imported from England

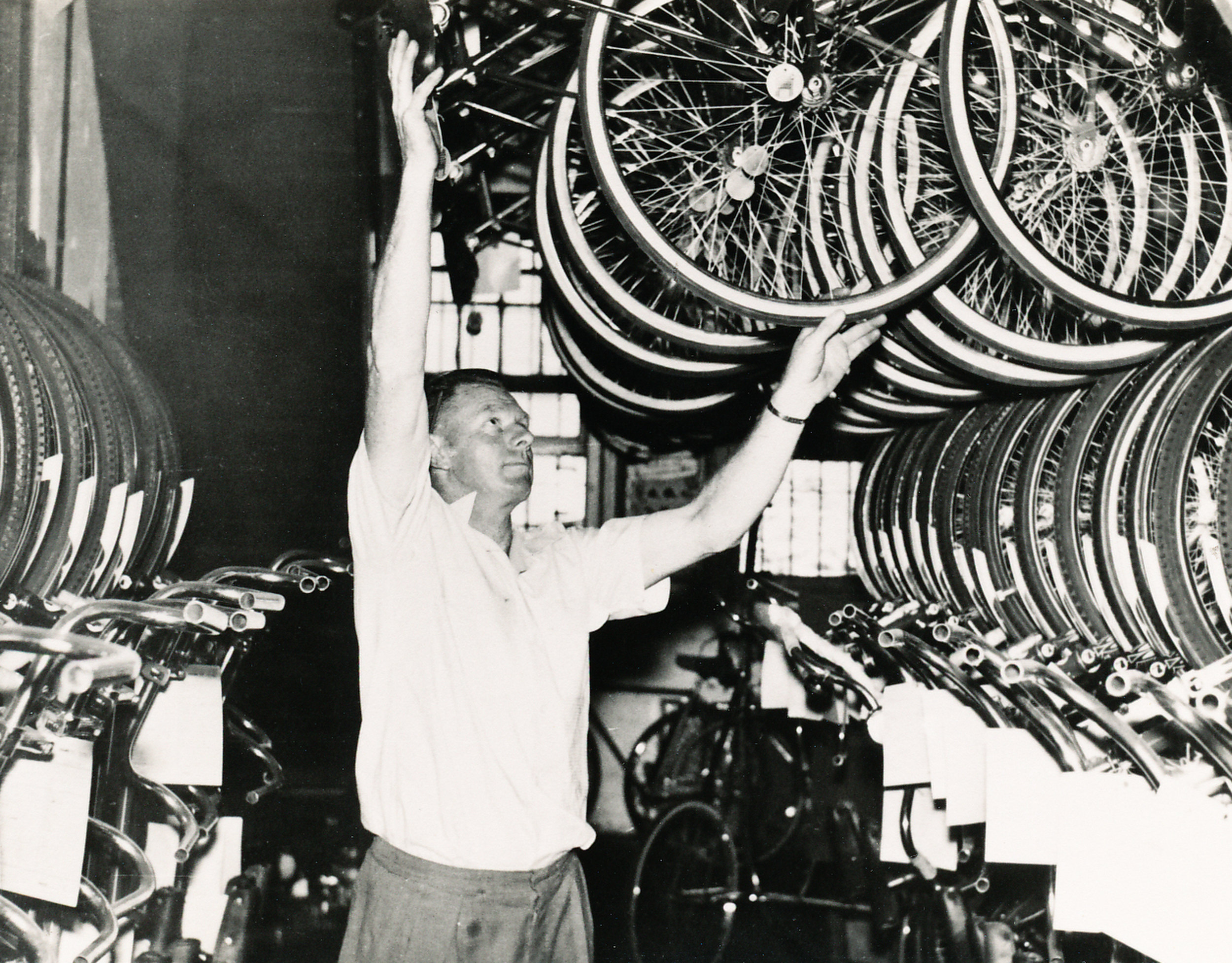

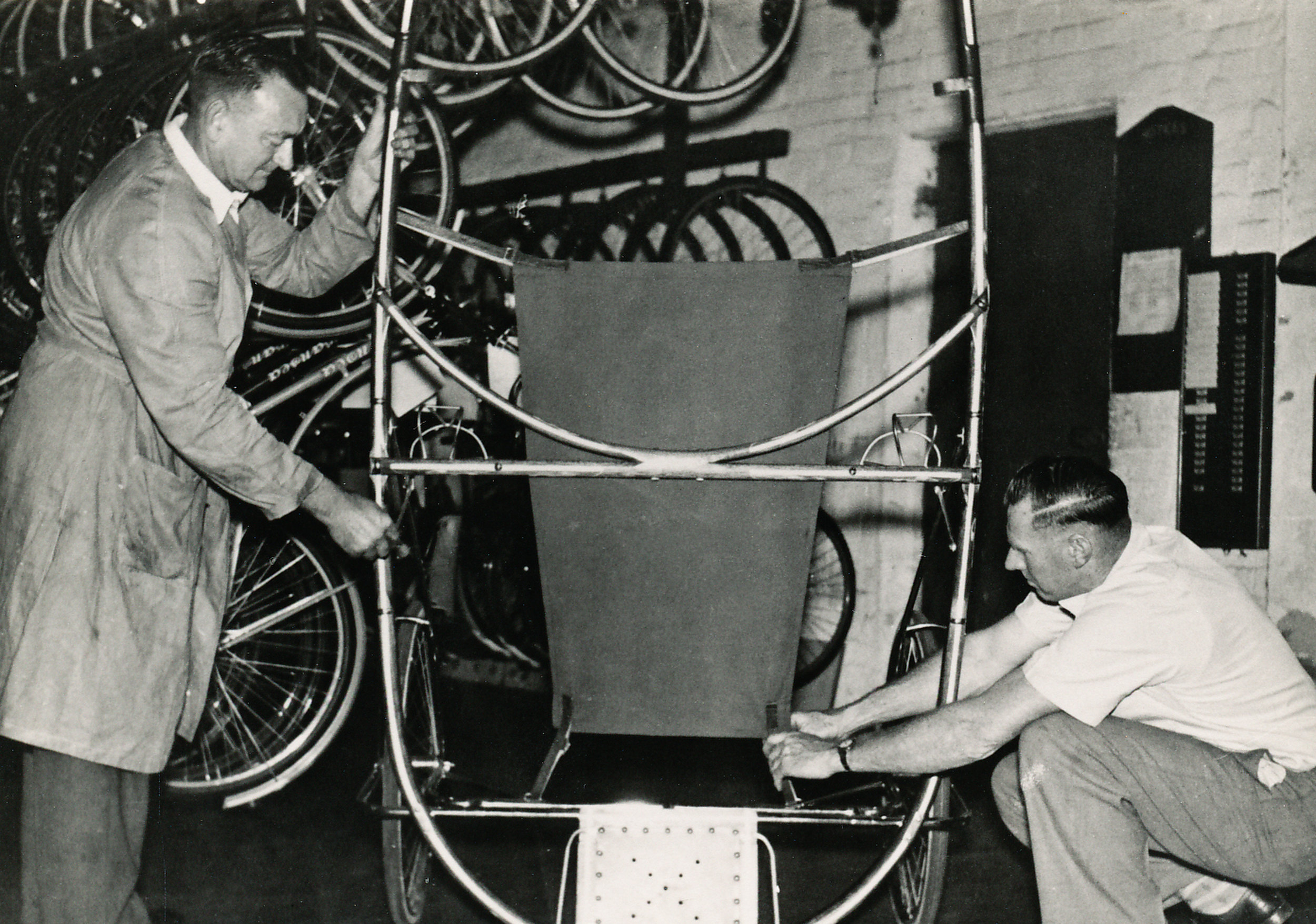

In the first year of trading Swansea made and sold all of 70 cycles. The great Wall Street crash of 1929, followed by the disastrous Depression years actually helped Swansea Cycles, as many people found bikes a great means of cheap transport that was healthy as well By 1939 Swansea Cycles had expanded to larger factory premises in Newman Street Fremantle, with 5000 square feet of floor space, a staff of 33, and a turnover of more than 1500 cycles a year, as well as trotting spiders and children's tricycles. There were also branches at Barrack Street, Perth, Kalgoorlie and Bunbury, and agents throughout the state. 1939 saw the introduction of the top end 4 and 5 Swan models.

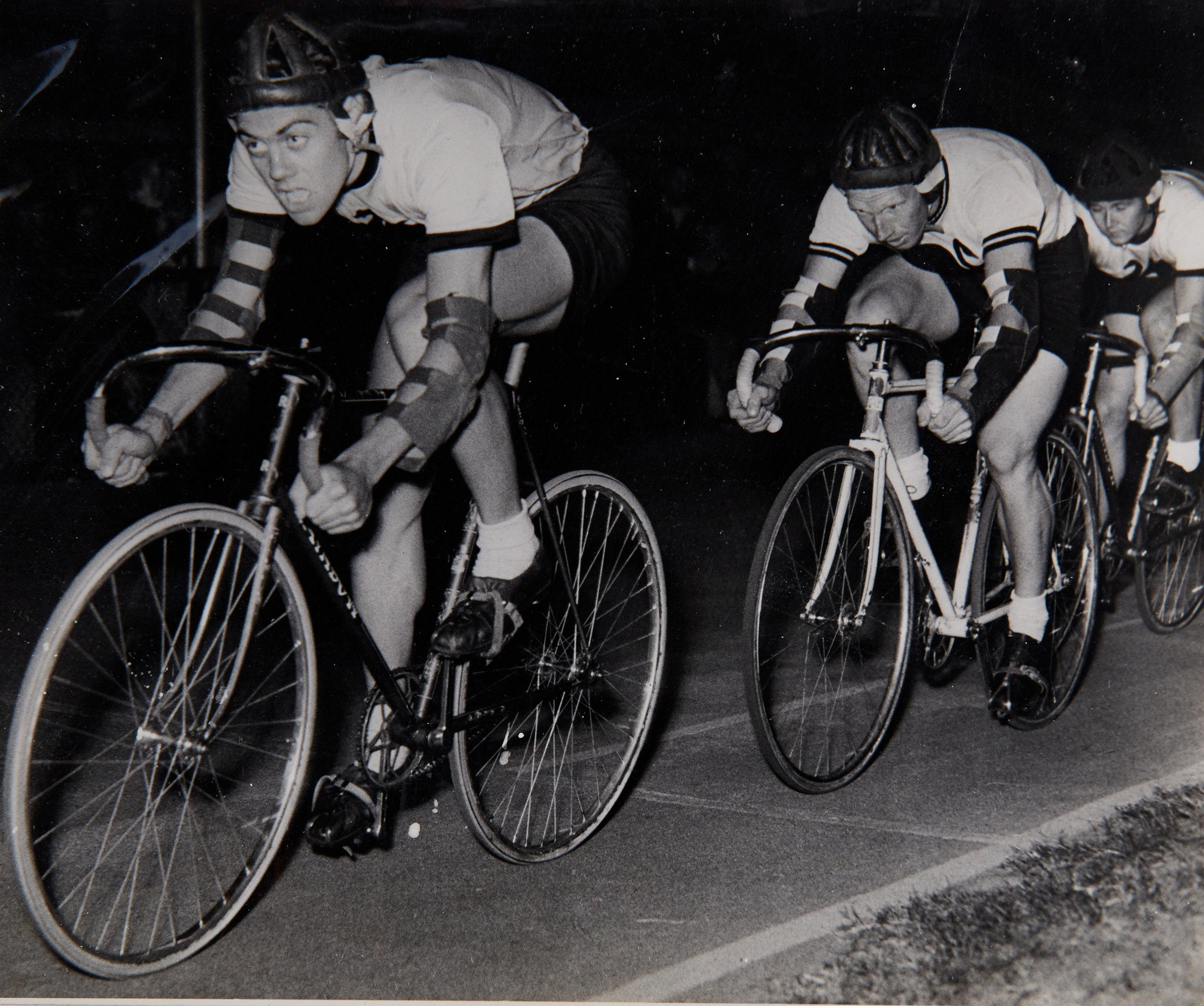

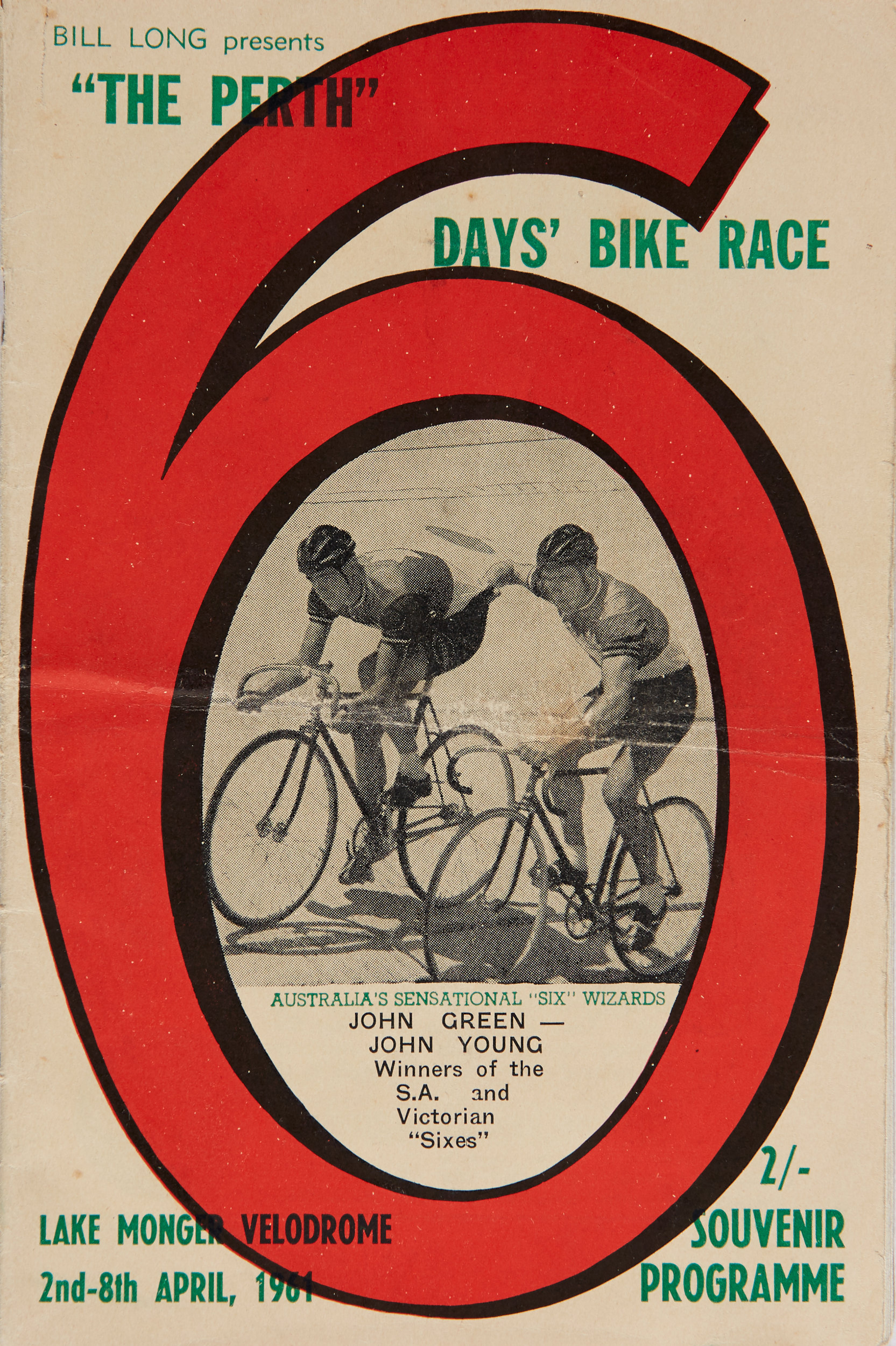

From the outset the firm saw the value to be obtained through racing their products, and actively sponsored many of the better sprint and distance riders in the state. Riders of the calibre of Dave Stevenson, Harold Durant, Jack Casserly, Sid Patterson, Merv Finn and countless others kept the Swansea name to the fore in the results of the big races. In those days programmes gave details of the machine being ridden, as well as the rider's name. One outstanding distance rider, Horrie Marshall, was the only WA rider to defeat Malvern Star's Hubert Opperman in a race. Horrie also won the prestigious Warnambool to Melbourne road race, on a Swansea of course. Swansea also sponsored the annual Swansea Road Race, from Perth to Armadale then on to the finish at Fremantle.

Second hand cycles passed through the factory before being offered to the public. World War II restricted the supply of important British made components for several years. This influence may explain the bias of refurbished machines in the war years. It has also been noted that the standard of finish was not quite up to pre war machines, but the same pride of workmanship was still evident, and there was still a strong demand for new machines. By the 1960's the motorcar had begun to make inroads into the cycle industry throughout the Western World, so Swansea's began selling electrical appliances, refrigerators, radios, as well as cycles.

The business closed in 1973. So a family firm that had given so much to Western Australian cycling, as well as supporting a staff that in its heyday amounted to some sixty-five people, finally closed its doors after more than forty years. Swansea cycles were regarded as one of the best available in Western Australia, and even today many are still to be found in owners' garages, taking pride of place, still giving their riders pleasure. Researched and written by Peter Wells and Stuart Bonser from an interview with Nell Baldwin.

Do you have a Swansea? Add it to the Swansea Register and receive a register tag.