Daniel Edward Sheehan was born at Lancefield, Victoria in 1864 and died at Hawthorn in 1928 aged 63 of diabetes.

The following article was published in the Western Mail published 19 May, 1899.

OVERLANDING - A CYCLE TOUR FROM MELBOURNE TO COOLGARDIE - 1899

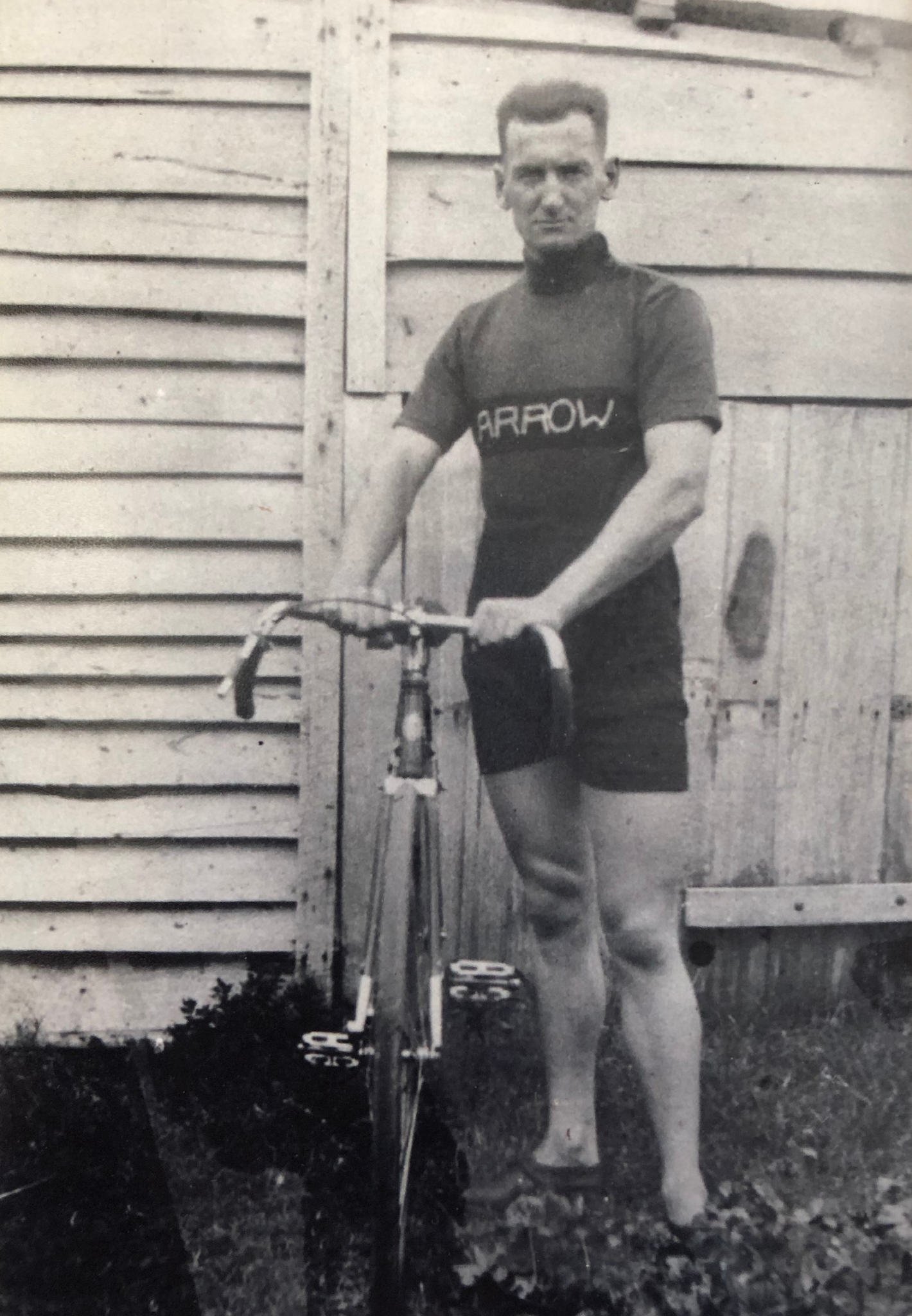

Mr. D.E. Sheehan, whose photograph we publish, gives the following opinion of “overlanding”. Leaving Melbourne on March 14th [1899], I rode against a parching “three quarter face” wind, which opposed me until well over the South Australian border. I travelled via Geelong, Camperdown, and Coleraine, over excellent roads through fertile and pretty country, which, however, is mostly locked up in large estates.

On the fifth day I reached Mount Gambier, a very pretty old South Australian town, surrounded by rich agricultural land. The picturesque Blue Lake, situated on an adjacent range of hills, is a sight to be remembered.

Beside the precipitous bank is a monument to Australia’s “sad, sweet poet,” Adam Lindsay Gordon. It seems incredible that even this daring man could have leaped a horse over the precipice known as Gordon’s Leap. Beyond Gambier the road to Adelaide runs north-easterly through some 150 miles of pastoral country, rabbit infested, lonely, and desolate looking. On the coast, about three miles distant, one can often hear the meaning of Gordon’s -

White steeds of the ocean, that leap with a hollow and wearisome roar

On the bar of ironstone steep, a cable’s length from the shore.

The pipeclay lake beds alongside the sometimes bad road are reputed to be excellent for cycling when dry, but the showery weather which prevailed prevented me from using them.

After passing Wellington the country improves, and is well settled, and after some stiff hill-climbing and descending one reaches Adelaide. From the metropolis northward to Port Augusta an excellent road traverses 220 miles of prosperous farming land, with small townships at short intervals.

When 28 miles from Augusta the front fork of my bicycle snapped while crossing a gully. I sought the assistance of a roadside settler, who, with a few old tools and much ingenuity, contrived an excellent splint, and then he hospitably invited me to share his Sunday dinner, which had been kept waiting meantime. Being unable to find anyone in Port Augusta who could repair the damaged arm I took it to a blacksmith, who patched it up with a piece of an old shovel blade.

I then turned westward through the dessert country with the motto “Coolgardie or bust”, nailed, so to speak, to the mast. Considering the immense extent, the country from here to the WA goldfield is of much the same pastoral character, barren looking and fairly level with monotonous miles of scrub, saltbush, and

scrubby eucalyptus, alternating with patches of sparsely grassed plain, and frequent patches of sand.

There are sheep stations of immense area at wide intervals, but they carry only from three to ten thousand sheep. Much of the station work, including the shearing, is done by aboriginals.

On Eyre’s Peninsula a succession of rainless years has driven many of the squatters from their holdings, which are now given over to rabbits and dingoes. Eyre’s Sand Patch, 165 miles west of Eucla, consists of 30 miles of loose fine sand, on which cycling is impossible, and a speed of two miles per hour fair walking.

When the tide is out nine miles of good riding may be had along the beach, which the road skirts. The overland route is fairly well watered by Government cemented tanks, roofed over to protect their being patronised by suicidally inclined rabbits and dingoes. The trouble is that the traveller is never sure whether the tanks ahead contain any water.

About Denial Bay an attempt was made to establish an agricultural settlement, but the drought has nearly ruined those unlucky farmers. An enterprising politician who started to canvass his constituency hereabout on a bicycle, got bushed, and after suffering much from thirst, was found “speechless”, but otherwise little the worse for adventure.

On two occasions, at Madura and at Fraser’s Range, I lost a day through taking a wrong track. The overlander should beware of the fiend who tells him, “You can’t go wrong old man, you can’t make a mistake if you try”. From what I heard every overlanding cyclist has taken a wrong track at one place or another. and three cyclists have been reduced to abandoning their machines.

Beside the track, near the head of the Bight, a mound of sand marks the last camp of an unfortunate swagman who perished from thirst last summer. My cyclemeter registered the total distance covered between Melbourne and Coolgardie, as 2,200 miles, and I was 38 days making the journey, including time lost. My longest day’s ride was 120 miles from Nullarbor to Eucla, and the longest stage without water 60 miles. My bicycle was geared to 60 and weighted, stripped, 33lb., kit and tools 10lb. extra.

I bought the bike, when new, five years ago for £15, from a well-known Melbourne firm of universal providers. I had it fitted with new tyres before starting on this tour, and it has proved to my satisfaction that a low priced bike is not necessarily an inferior one. I confess that I was not sorry when the tour was finished, and have no intention of cycling it again.

Collected and corrected from Trove by Daniel’s grand niece Lynnette Hammet.