Our Hidden Cycling History

STORIES FROM WA IN A TIME WHEN BICYCLES WERE A VITAL PART OF OUR TRANSPORT MIX.

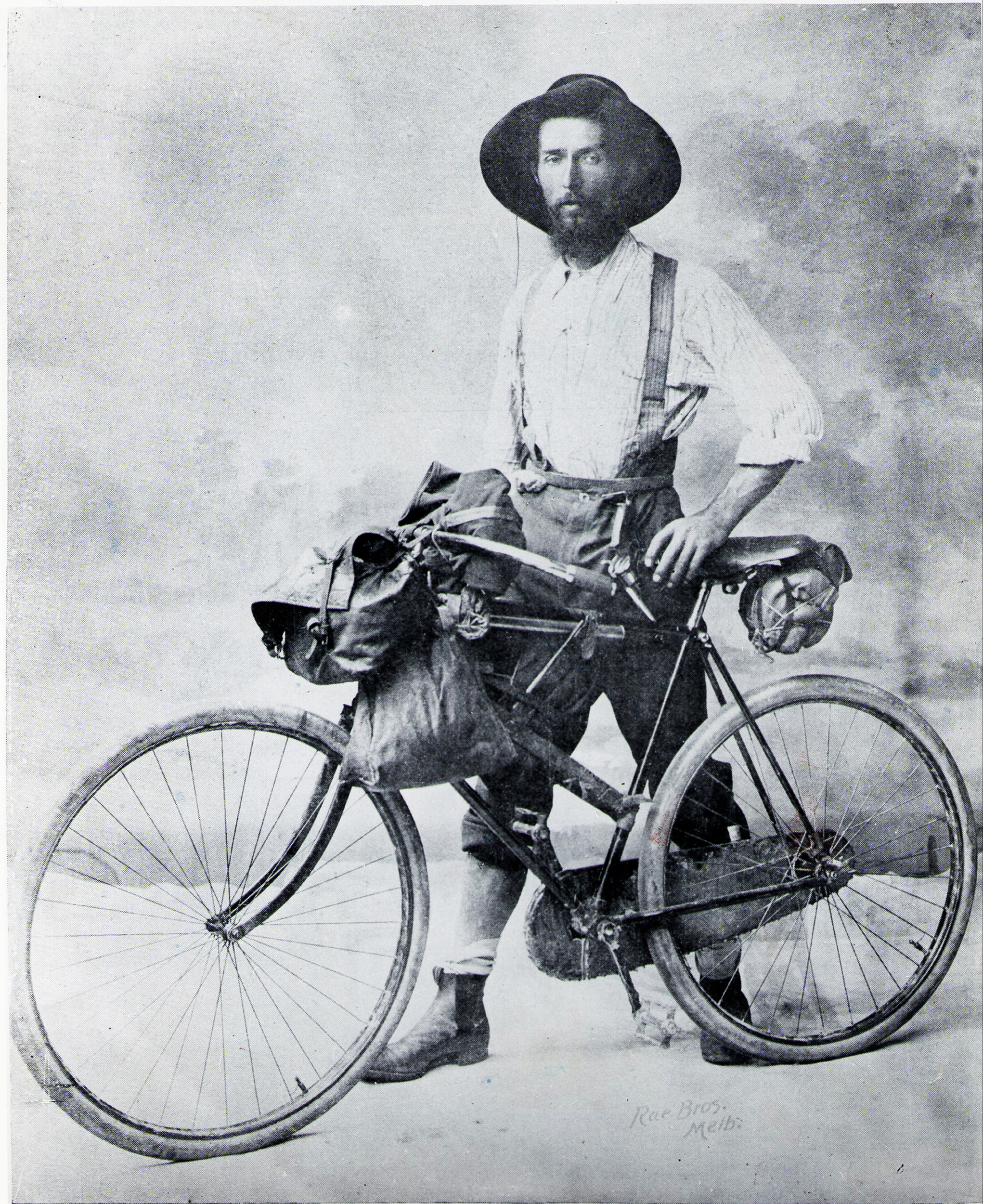

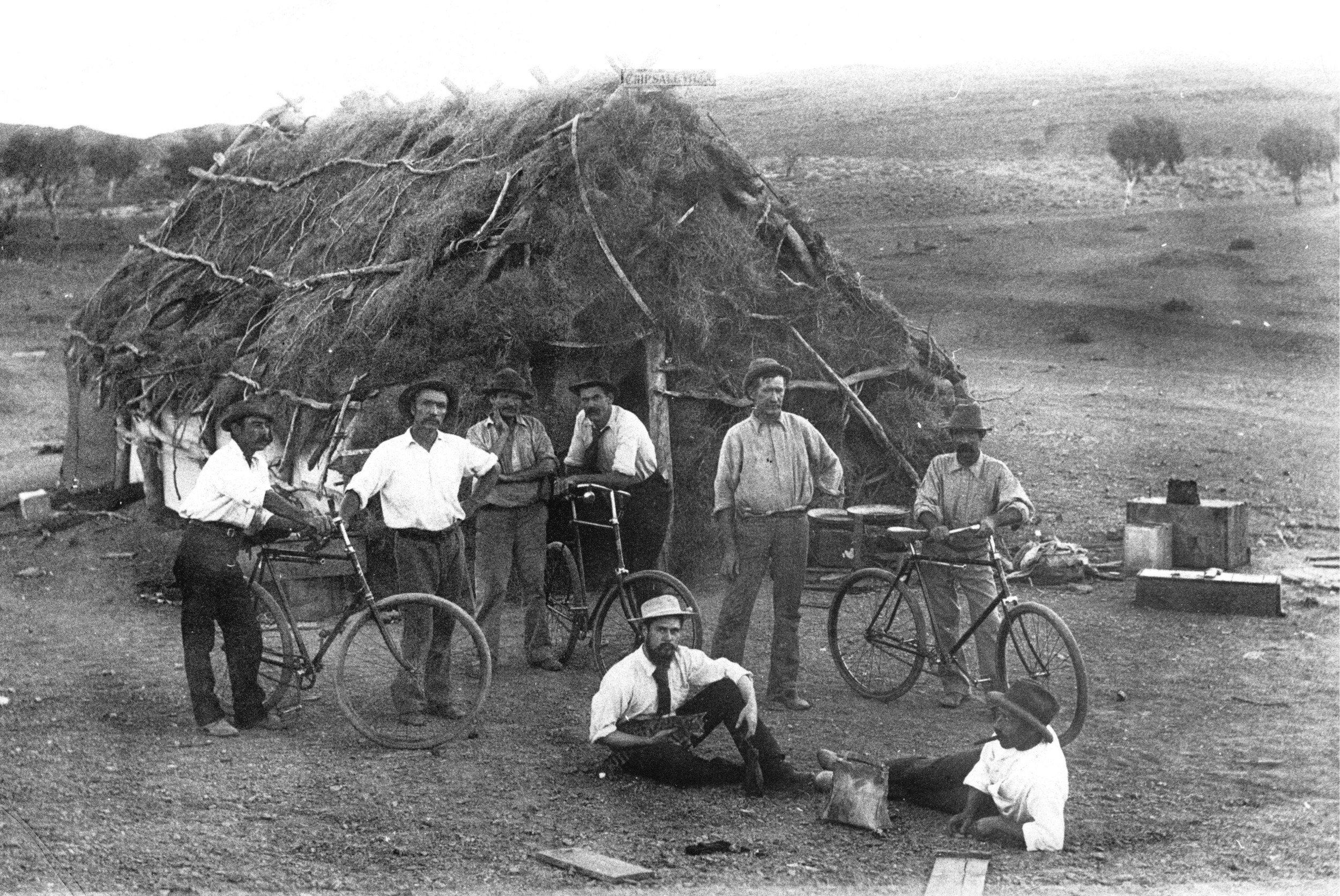

Although much of Australia had been explored by 1890, the population was mostly scattered around a few sprawling coastal cities. In these pre-car days there was a need for travel between the widely spaced settlements and isolated homesteads, as well as within low density urban areas.

The invention of the “safety” bicycle proved a landmark in the history of personal transport.

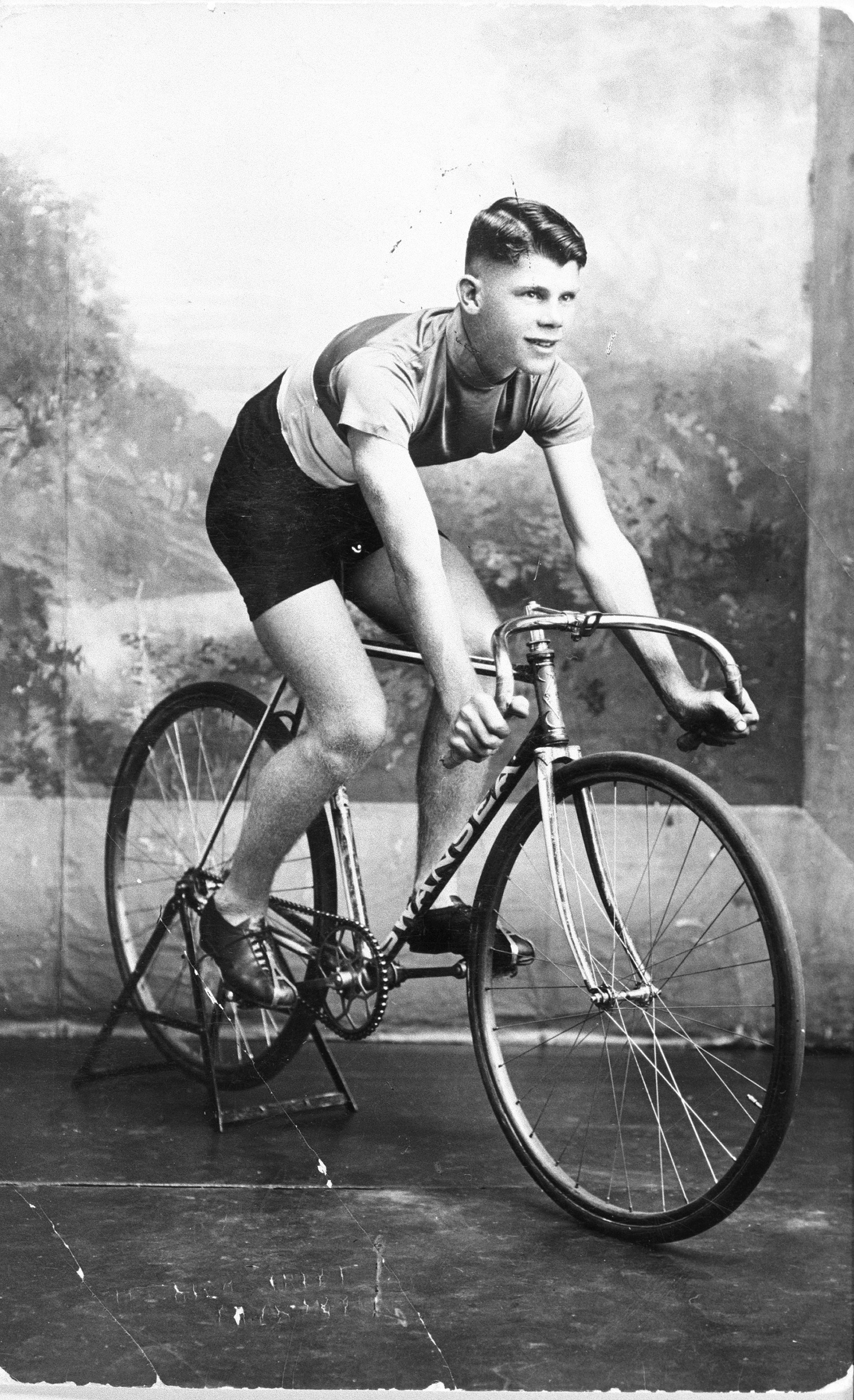

Its speed, safety, ease of riding and low cost captured the imagination of many Australians and the country found itself in the midst of a worldwide bicycle boom. By mid-decade, cyclistes (as female riders were commonly known) were not unusual on our streets; churches questioned the morality of Sunday cycling; doctors debated the effects of riding and bicycle dealers were gaining reputations formerly attributed to horse traders.

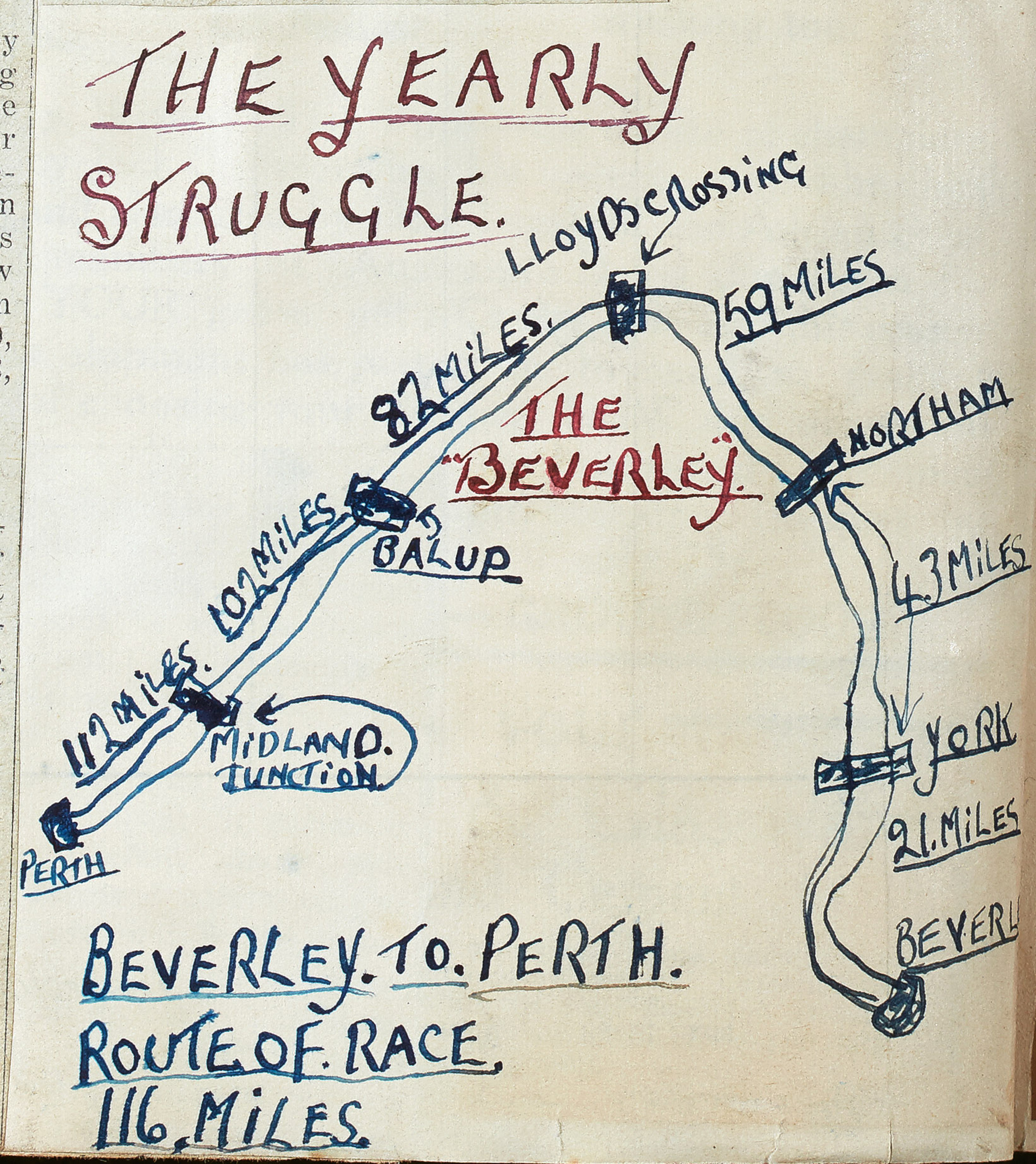

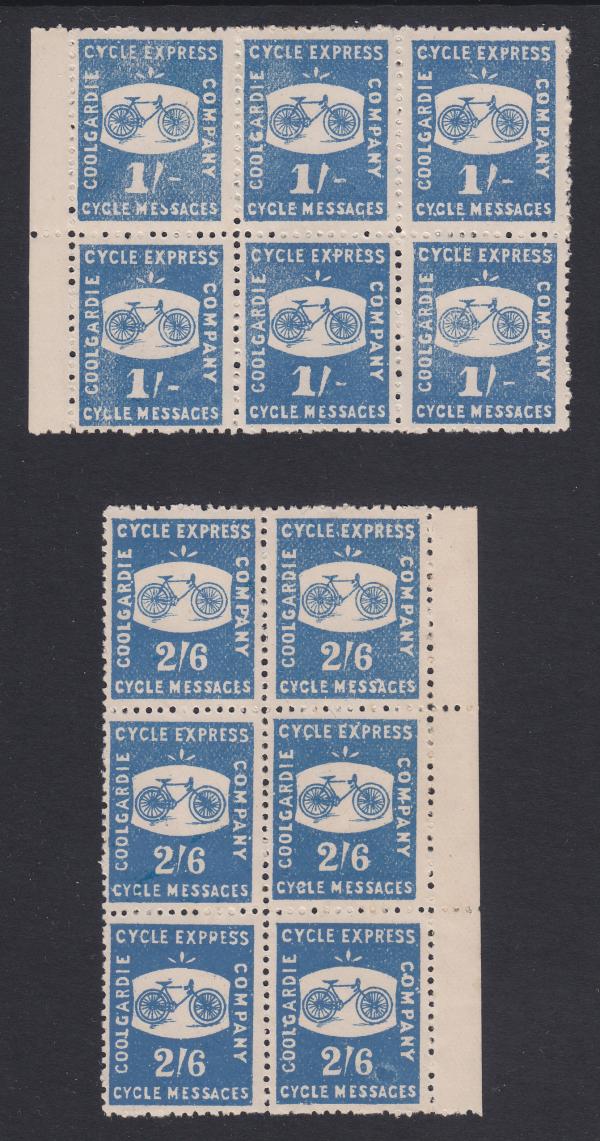

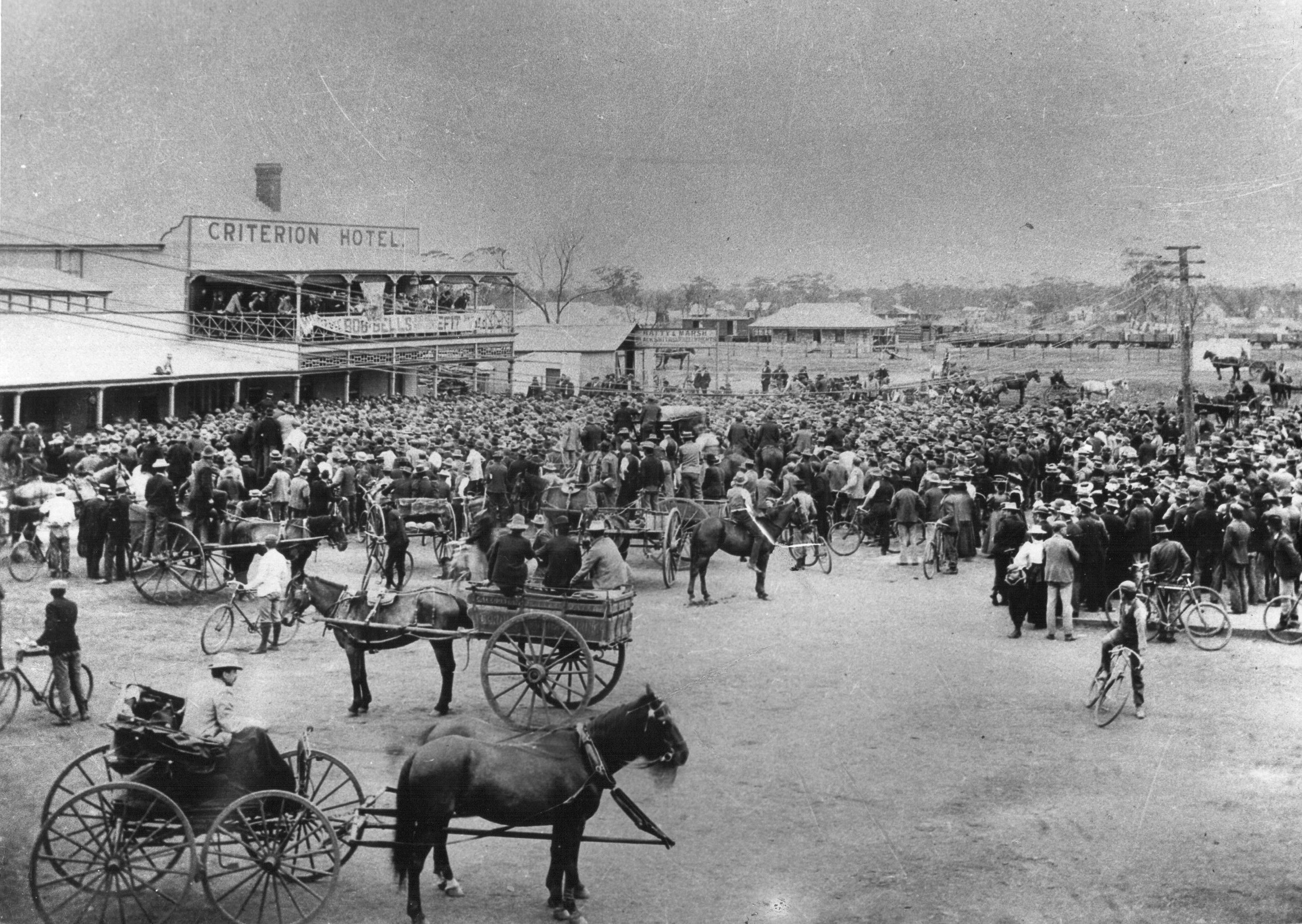

Our local cycle industry flourished until after World War II. WA boasted almost 100 bike building shops, the largest of which, Swansea, boasted 60 employees at their peak. This building was home to WA’s first registered cycling club ‘The League of WA Wheelmen’. Thousands of people attended track races, orthe finishes of long-distance cycling events, held co-incidentally (if not mercifully) at popular watering holes.

Transport cycling slowly went out of vogue as car ownership rose. The cycle clubs that once dotted suburbia and country towns packed up the bike racks decades ago. Encouragingly, a recent rejuvenation in recreational cycling has seen gents with trouser clips and gals in breezy skirts cycling through our city streets once again.

Our Hidden Cycling History reopens archives, albums and back sheds to reveal 7 uniquely West Australian stories centred around this wonderful mode of transport – Cycling.

The Western Australian Historical Cycling Club would like to thank the following people and organisations for their support of our first multi-day exhibition.

The exhibition has been partially funded by Bike Week and the Department of Transport. We would alos like to acknowledge the support of the WA Museum, and Reece Harley from the Museum of Perth.

We are indebted to author Jim Fitzpatrick for the use of his research and for allowing us to quote from his book "The Bicycle in the Bush".

Tracy Graffin is responsible for the superb graphic design of the interpretive panels and publicity collateral.

The Manning Men's Shed built plinths for the four floor standing bikes.

Murray Hall from Track Cycling WA officially opens the exhibition on March 3rd 2016.

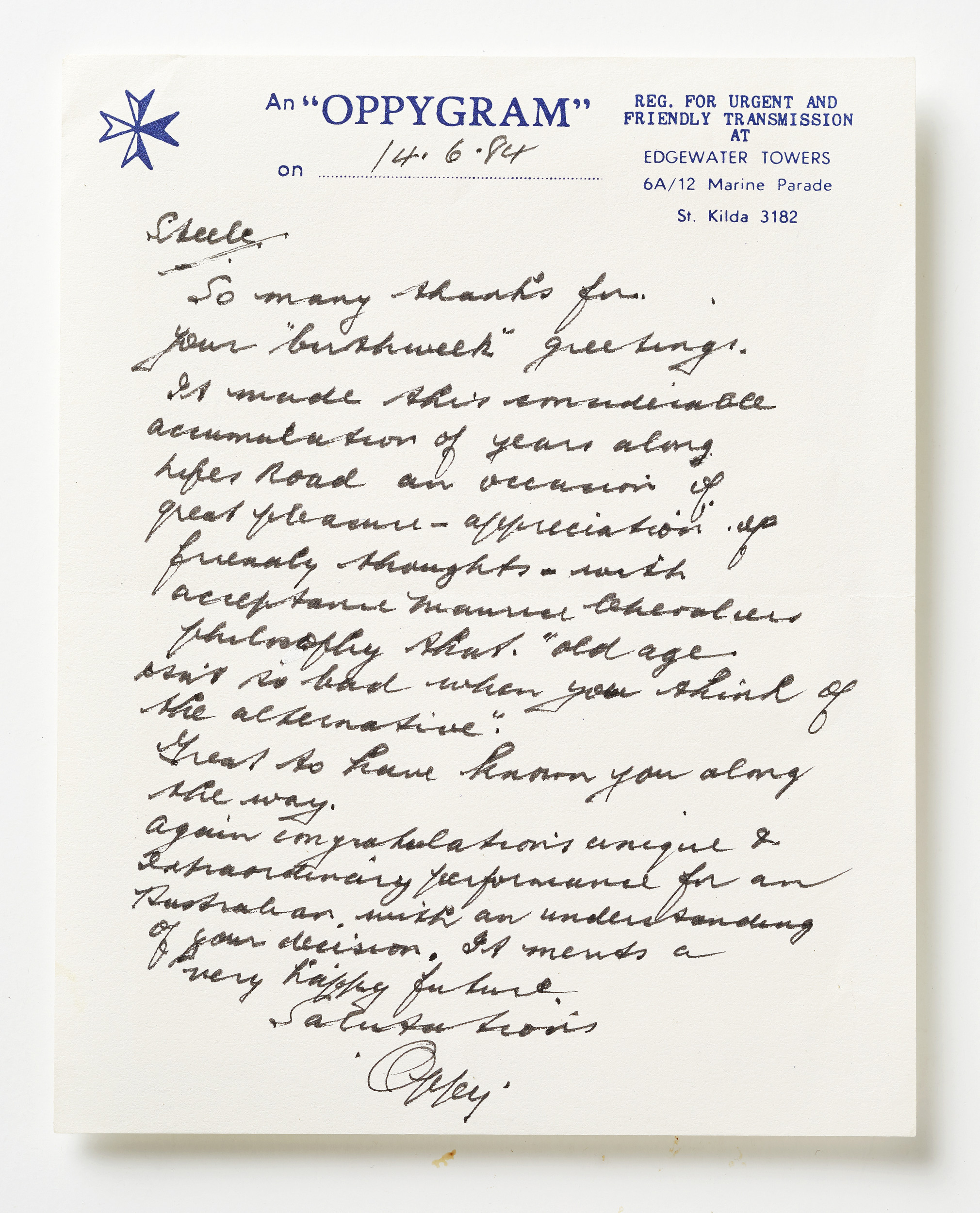

Generous gifts and loans to the club for the exhibition have been made by Steele Bishop, George Kingsley, Bruce Hartley and Cliff and Carolyn Garavanta.

A number of club members have made loans as well, Mal and Myrene Bell, Merv and Dawn Thompson, Kym Murray, Tim Eastwood and Robert Frith.

The WAHCC exhibition team was Dennis van Gool, Tim Eastwood, Kym Murray, Robert Frith, Viv Cull and Malcolm Bell.